.tmb-768v.png?Culture=en&sfvrsn=54737d84_1)

Providing essential noncommunicable diseases services to vulnerable populations in Yemen

Key learning points

Integrating triage spaces and staff as a standard measure, could help avoid service disruptions and keep facilities safe for vulnerable patients. Successful implementation of triage in a small facility provided a model for neighbouring facilities. Staff and patients came to accept it after initial resistance. Continuing this system beyond the pandemic would provide a safer clinical environment for staff and patients, and would help prioritize health care delivery based on need.

Background

The long-standing conflict and siege in Yemen have led to severe deficiencies in the provision of health care to the country’s population, with only 50% of health care facilities operating across the country, and this before the COVID-19 pandemic. Poverty, roadblocks and the unstable security situation prevented people from travelling to cities to seek health care. Those unable to afford health services would go to facilities operated by humanitarian organizations. Therefore, these facilities serve some of the most vulnerable populations.

Noncommunicable diseases (NCD) are responsible for more than half of the deaths in Yemen. Utilization statistics reflect a high demand for NCD services. However, there is less donor support for NCDs due to competing priorities. For example, in Sana’a, a city of four million inhabitants, there are just two organizations providing NCD health services. Furthermore, facilities offering NCD services are often difficult to access for those not living in cities.

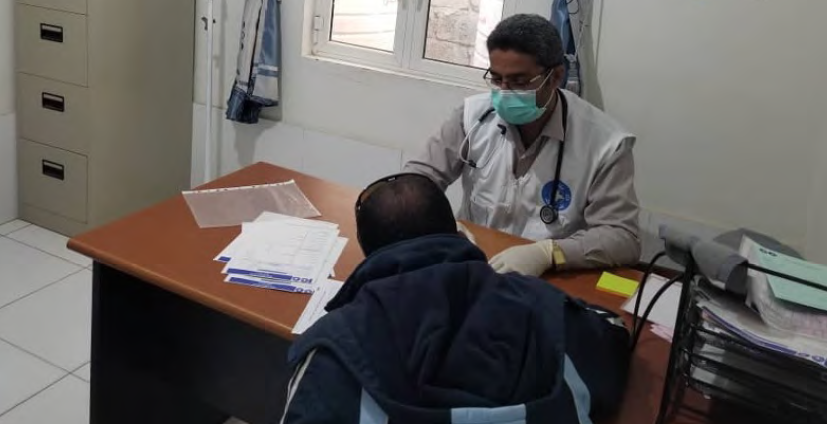

MdM Medical doctor in Sawan receives and treats NCD patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Source: Médecins du Monde

Impact of COVID-19 on essential health services

Official data on the spread and extent of COVID-19 in Yemen are limited. But anecdotal accounts suggest that there has been widespread community transmission and a high death toll. There have been shortages throughout the supply chains during the pandemic, although disruptions to essential health services preceded the pandemic, and were mostly due to administrative problems and difficulties in air freight and delivery. The medication shortages worsened due to the disruption of international transport.

What was the intervention or activity?

When the pandemic started taking hold, some humanitarian organizations played an important role in supporting the maintenance of NCD services. One example is Médecins du Monde (MdM), which runs medical and advocacy programmes for vulnerable populations in areas in crisis. Since 2016, an MdM medical team has been operating the Sawan health facility in Sana’a. The facility serves a marginalized local community of Afro-Yemenis (Al-Muhamasheen) who cannot pay for health care. About 30-40% of cases seen daily at the facility are people living with NCDs.

One of the first measures implemented was effective triage. A house adjacent to Sawan health facility was rented and repurposed into a triage and isolation station. An extra COVID-19 budget was provided by donors and additional staff were hired to cover triage. Patients were seen by a nurse and physician to have their temperature checked and to answer screening questions. They would then be directed to the correct place to receive the service needed. The triage station staff would also explain the one-way system. Those who fit a COVID-19 case definition were directed to temporary isolation rooms for further assessments and education.

In addition to implementing triage in the facility, NCD patients requiring regular follow-up received an appointment card at the end of their visit stating the date and time of their next follow-up visit, in order to reduce crowding in waiting areas. They were also given a number to contact if they needed a teleconsultation and a 2-3 month medication supply when available.

The newly developed triage room in Sawan Health Unit. Source: Médecins du Monde

How did this intervention/activity contribute to the maintenance of EHS?

Through triage, health care facilities were able to protect people living with NCDs and ensure their safety, given that they are one of the most susceptible groups to COVID-19 and its complications

What were the key challenges involved? How were these challenges overcome?

There was no proper system for triage prior to COVID-19 pandemic in MdM-supported MoH facilities. This led to crowding, long waiting times, and disorganized patient flow. Implementing triage for COVID-19 was a big challenge. Resistance was encountered from both patients and some health care providers who believed that triage tents or buildings were isolation centres that would spread infection. The fear, confusion and mistrust at the start of the pandemic sometimes reached the point of citizens throwing rocks at the triage tent. Education campaigns from the MoH and the authorities were absent, and awareness therefore needed to be communicated at the facility level.

While Sawan Health Facility eventually established an effective triage system, it was more challenging for the MoH to persuade patients to accept it.

Other challenges were related to personal protective equipment (PPE) and the shortage of health care providers. MdM was able to secure a shipment of PPE. However, on monitoring their use, it was found to be low.

With rising rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths among health care workers, there was a lot of absenteeism in MoH facilities due to fear. However, there was no staff shortage in MdM-facilities because attendance was monitored and if a provider needed to self-isolate or fell ill, there would be a backup on call to cover their shift (male and female physicians, nurses and laboratory staff).

Please indicate any areas of support you require in the maintenance of essential health services

MdM faces challenges to sustain this system due to budget constraints. Support provided by international NGOs and donors is crucial to enable the provision of essential health services during these particularly challenging times.

The MdM medical supervisor training the triage staff to use personal protective equipment in a triage area at Sawan Health Unit. Source: Médecins du Monde